Were the birds in the trees and the crying baby in the house really that much louder as we cruised by on our bikes during the lockdown? Or was it really that the world was much quieter?

Yes it was. Really. Much. Quieter.

A fascinating study has confirmed that our exposure to environmental noise dropped nearly in half during lockdowns.

We know because our watches were monitoring.

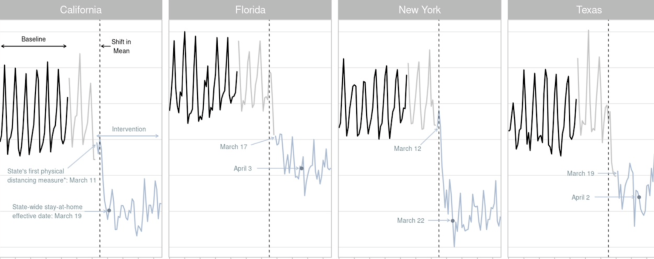

Researchers at the University of Michigan School of Public Health and at Apple looked at noise exposure data from volunteer Apple Watch users in Florida, New York, California and Texas.

The analysis, one of the largest to date, included more than a half million daily noise levels measured before and during the pandemic.

Recent model watches and headphone/iphone combinations from Apple monitor environmental noise to help prevent hearing loss.

Many riders have observed how much more peaceful riding was during lockdown without the constant roar of cars, trucks and motor bikes.

Chronic exposure to sound not only results in hearing loss, it is associated with cardiovascular disease and other health impacts

Daily average sound levels dropped approximately 3 decibels during the time that local governments in the US made announcements about social distancing and issued stay-at-home orders in March and April, compared to January and February.

“That is a huge reduction in terms of exposure and it could have a great effect on people’s overall health outcomes over time,” said Rick Neitzel, associate professor of environmental health sciences at University of Michigan School of Public Health.

“The analysis demonstrates the utility of everyday use of digital devices in evaluating daily behaviors and exposures.”

The average levels of noise exposure dropped dramatically after lockdowns started in early March in New York, California and later on in Texas and Florida. More than 500,000 daily noise levels from about 6,000 participants were utilized in the study, the largest dataset for individual noise exposures analyzed to date.

“California and New York both had really drastic reductions in sound that happened very quickly, whereas Florida and Texas had somewhat less of a reduction,” Neitzel said.

Initially, the largest drop in environmental sound exposure was seen on the weekends, where nearly 100% of participants reduced their time spent above the 75 dBA threshold (a sound level roughly as loud as an alarm clock) between Friday and Sunday.

“But after the lockdowns, when people stopped physically going to work, the pattern became more opaque,” Neitzel said. “People’s daily routines were disrupted and we no longer saw a large distinction in exposures between the traditional five working days versus the weekend.”

These data points allow researchers to begin describing what personal sound exposures are like for Americans who live in a particular state, or are of a particular age, or who have or do not have hearing loss.

“These are questions we’ve had for years and now we’re starting to have data that will allow us to answer them,” Neitzel said. “We’re thankful to the participants who contributed unprecedented amounts of data. This is data that never existed or was even possible before.”