Bike-friendly communities

Rideables are challenging traditional transport systems, the laws that regulate them and the proper allocation of space on our streets.

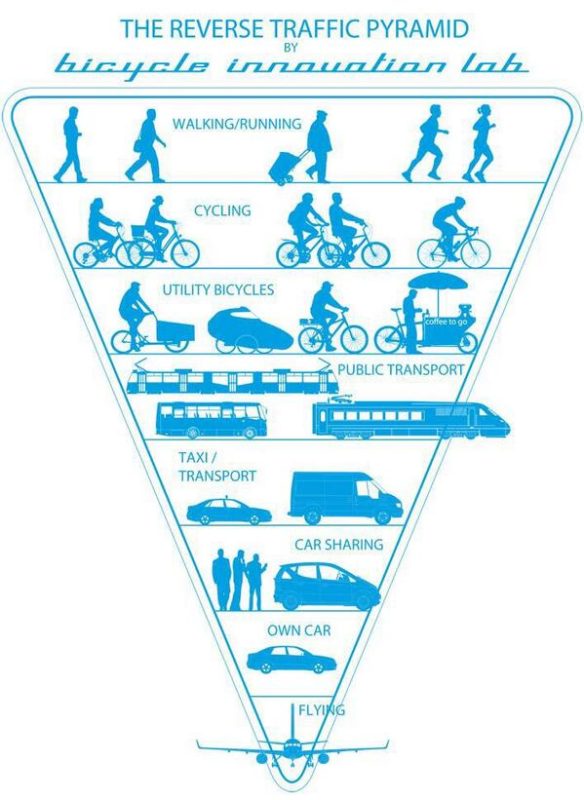

In 2011, Bicycle Innovation Lab, an independent bicycle culture house out of Copenhagen, released their “reverse traffic pyramid”. The aim of the pyramid was to suggest an approach to city and urban planning that appropriately prioritises active travel and aims to decrease the congestion and pollution of a car-centric city. In the pyramid, walking and cycling is prioritised above other modes due to the wide-ranging health, economic, environmental and cost benefits. It did a great job of succinctly summing up what should be happening in our communities. However, as new technologies diversify and increase our transport options, populations continue to grow, and travel habits begin to change–city planning, and legislation will inevitably struggle to keep up. We are seeing this around the world with the rapid increase of personal electronic ‘rideables’ such as electric scooters, segways, hoverboards and throttle e-bikes. Rideables are challenging traditional transport systems, the laws that regulate them and the proper allocation of space for so called first and last mile transport options. It raises some important questions for advocates, governments and planners – where do rideables like electric scooters belong and do our laws need to adjust?

An integrated transport system with varied transport modes that connect and complement each other is important for a community’s mobility, liveability and efficiency. It recognizes that there’s a place for all kinds of transport. When thinking about how rideables fit into this transport mix, it’s important to consider the wide-ranging benefits, impacts and risks. While rideables may help with issues of traffic congestion, reduce the need for parking space and are for the most part eco-friendly, they don’t address the growing danger of physically inactivity that is crippling our population. In fact, many of the electric scooter companies target “last mile” transit, raising concerns that they will replace active walking trips rather than get cars off the road.

The benefits of active transport must remain top priority. Not only for the undeniable benefits to health (physical and mental) and the environment, but also the varying economic benefits emerging from studies of bike-centric cities around the world. “Bicycle infrastructure makes so much economic sense that it can accurately be described as a health investment,” claims Elly Blue, author of Bikenomics: How Bicycling Can Save the Economy. Researh from Portland predicts their investment in bike riding result in health care cost saving of up to $600 million by 2030. Meanwhile in the bike-centric cities of Denmark, every kilometer travelled by bike instead of car means €1 (AUD 1.60) gained in health benefits. Not to mention the infinitely cheaper cost of building and maintaining places for people to ride compared to places for people to drive.

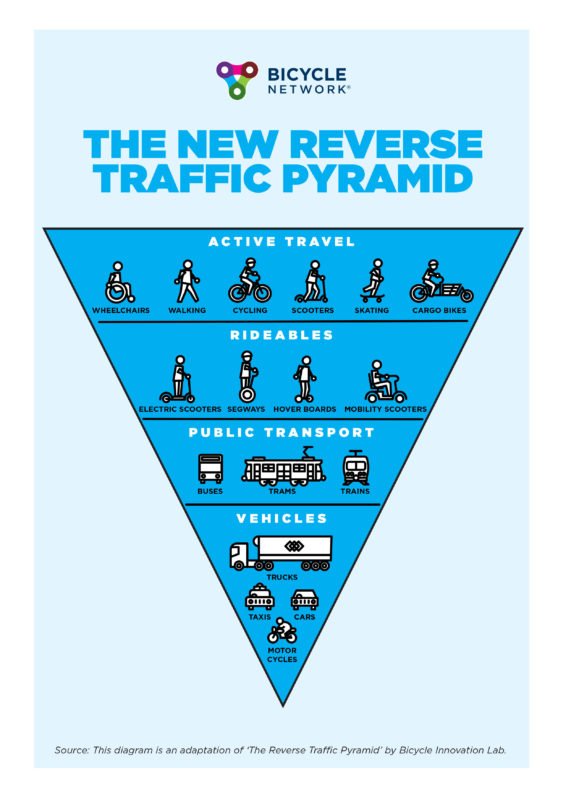

With the distinction between sedentary and active travel in mind, Bicycle Network has designed a new reverse traffic pyramid which divides transport modes in to four distinct groups to prioritise the multimodal transport planning of our cities. Based on the original reverse traffic pyramid, each mode of transport was rated across categories of cost, space, health and time– with time taking into consideration distance travelled (e.g. active travel scored high for short trips, and PT or vehicle scored high for long trips).

Click the image above for a larger version.

The challenge now is to adapt rules made predominantly to govern cars, pedestrians and bicycles to incorporate these convenient new devices, and keep our roads and paths as safe as possible for all users. Already we’ve seen Queensland introduce a range of new road rules as “a response to the growing popularity of electric scooters, electric bikes and other forms of personal transport,” said transport and main roads minister Mark Bailey. A 25km/h speed limit, mandatory helmet wearing, riders over 12-years-old only and a ban from use on Brisbane roads are among the announced changes. As other states struggle with the question of where these devices fit into their transport systems, personal mobility service providing companies like Lime are eagerly knocking on the door. In the US, New York City are also actively struggling to update existing laws made predominantly for car, bicycle and foot traffic to incorporate devices that don’t neatly fit in the existing paradigm. An abundance of short-named electric scooter share companies like Skip, Scoot, Lime, Bird and Jump continue to pop-up, often short-lived, in other American cities to mixed reactions, with Skip and Scoot recently granted one-year trials in San Francisco.

Bicycle Network remain supportive of any transport initiative that gives more people easy access to healthy and sustainable transit. We will continue to keenly monitor how different states in Australia approach responsive legislation and long-term infrastructure changes to accommodate the growing market of rideables. However, making it easier for more people to ride bikes and choose active transport will always remain our number one priority.

Prioritising transport

The reverse traffic pyramid

Rethinking the pyramid

The new reverse traffic pyramid

The rideable reaction

Bicycle Network’s position