Keen bike rider Richard Langley has sent us what’s left of the letters his grandfather Don Charlwood wrote to his wife’s Canadian relatives about their cycling trip around Tasmania in 1947.

Unfortunately, only the first week of his account has survived. It covers the departure from Melbourne, ride from Burnie to Devonport, train to Launceston then on to Herrick, and the ride from Herrick through the North-East.

We love a bike packing story and thought you might too, so have included excerpts which will have you wondering if some things ever change and how much luckier we are to have the Spirit, gears, disc brakes and more paved roads these days!

It’s also interesting to read they pass other groups riding around the island on a holiday, showing Tasmania’s position as a cycling touring destination has long been held.

Don went on to become a recognised Australian author, starting with his biography of navigating fighter planes in World War II and then many other non-fiction books about his war experiences, air traffic control and maritime history. His classic coming-of-age novel All the Green Year was made into a TV series by the ABC in the 1980s, and was awarded a Member of the Order of Australia for his services to literature in 1992. For further information on Don Charlwood’s books, see the Burgewood Books website: www.burgewoodbooks.com.au

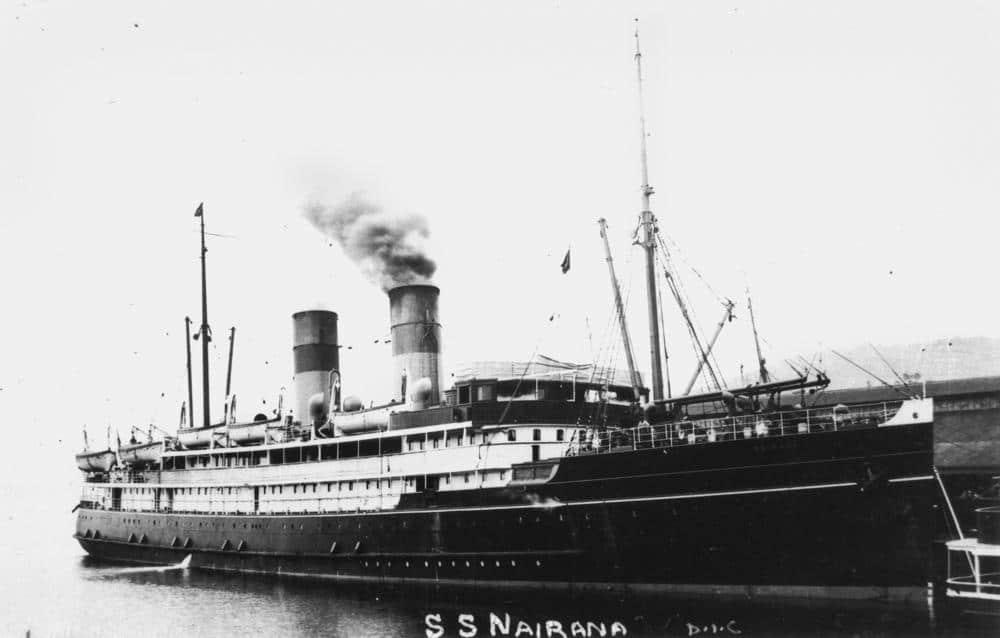

Image of the Nairana ferry: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

To set the scene, Don and wife Nell East, left Melbourne on 14 January in 40 degree heat for a “leisurely outdoor holiday” to help Nell recover from an illness. After the holiday they had pledged to get to work on finishing their house under construction and starting a family (luckily for Richard, that plan was carried out).

Our ship, if she can be graced by such a name, was the “Nairana”. She lay at No. 10 North Wharf on the picturesque lower reaches of the Yarra, among warehouses, fish markets and gas works.

When we returned to the deck the scenery had changed. We were now in abbatoir and soap factory country, with here and the roofs of blood and bone manure manufacturers against the horizon. The river had widened to perhaps 150 yards and its waters had changed from yellow to brown.

…

On deck a cool breeze had tempered the sun; but in our cabin the temperature was still 104 [40 degrees Centigrade]. It was a dreadful cabin somewhere below the waterline, closely surrounded by other dreadful cabins, whose occupants’ intimate conversation we could hear clearly.

The Tasmanian boats are flat-bottomed to allow them to enter the rivers at Launceston and Devonport, consequently they roll easily. It began rolling this night. It appeared to keep the children in the next cabin awake. They cried incessantly, till, at 1:00 am, we heard some smacks, some irritable complaints from a husband and then, in perfect time with the roll of the boat, the mother, working slowly backwards through her meals of the past week.

…

We ate a substantial breakfast, then went on deck. We were docking at Burnie and even at this early hour a few locals were seeing the boat in. The town stood on a hill above the wharves and above the town rose higher hills which continued as far to the east as we could see, falling steeply to the sea. Though we could plainly see our coast road and lighthouses on distant points, I kept feeling that here was unexplored country and that we would be the first people to go the way we planned. The early sun added to this feeling of mystery. It was not yet 6:30 am.

I sent our case of respectable clothes to Hobart by train, while Nell began tying on our loads (helped by advice from the decks of the Nairana). At 7:30 am we departed. Somewhere just ahead of us were four girls, also setting out on bicycles.

We saw only that part of Burnie facing the sea: old, stone buildings belonging to earliest Tasmania. Completely deserted as they were at this hour they intensified the atmosphere of another century that seemed to me to lie over the whole scene.

We passed the last shops and then a large new paper mill. The road surface was perfect, little indication of nearly all our tomorrows.

We passed the first mile post, - L. for Launceston, 96.

“We’ll soon cut those down,” cried Nell happily, “Gee my load feels good. You told I’d notice a big difference with it on”.

And then we came to our first hill, up past a solitary house, past a navigation sign on a rocky headland; past a squat, white lighthouse. I was ahead and tiring quickly; but Nell was still pushing along determinedly. After a few more yards I got off, saying peevishly, “you can push if you like – I’m not too proud to walk”.

Nell got off with visible relief. “I was nearly done. Let me lead on the hills, Daddy, it’s bad for my morale to see your big legs going on and on. And my jodhpurs are rubbing my knee. I should change to shorts”.

My morale improved, too. “I’ll lead going down hill,” I suggested, “because my brake won’t hold as well as yours and you lead up hill”. Such was our arrangement for the whole journey.

Though our road seemed as close as possible to the sea, Tasmanian engineers had contrived to run the railway even closer; so that as we rode along it was right beside us, between us and the waves.

A comical, asthmatic little train came hustling along this line, appearing as though it were running rather than riding on rails. It swayed and jerked and spluttered, gave a shriek as it saw us, the driver waved, then the whole show vanished round the next point, as though about to plunge into the water.

There were settlements along the way; but had it not been for their station signs, we would have passed them unnoticed – Blythe, Howth, Sulphur Creek and so on.

Our way was steeply down hill, back to the coast, to a sleepy old town called Penguin, possessing a main street a mile long, though its activities need only have occupied a hundred yards.

All the way to Penguin we had passed side roads turning inland to such euphonious places as Riana, Camena, Cuprona and Natone. At Penguin was the last of these turn offs. Our own road swung inland into dairying country, with here and there large fields of tomatoes growing.

We had lost the company of both the sea and the comical railway; but after seven or eight miles we descended on to a broad river, called, I think, the Leven. On its far bank was the town of Ulverstone, a place of, perhaps two thousand people.

…

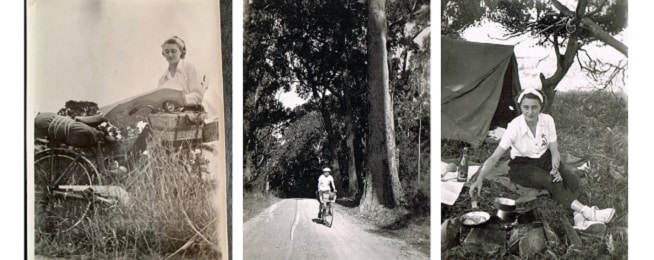

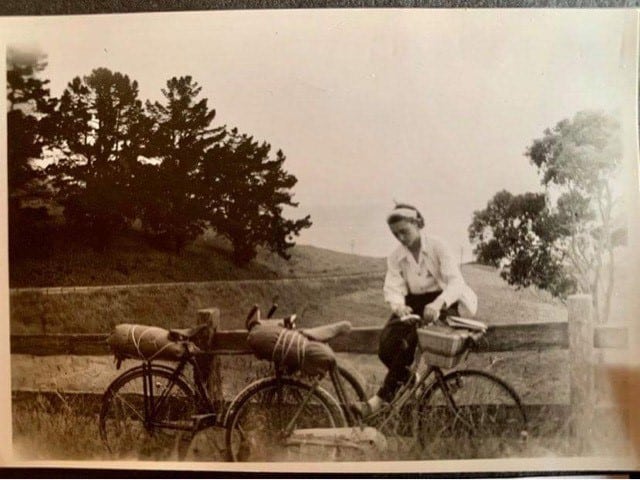

Image: Nell next to the two loaded bikes

Tasmania is reputed to be another England; but I could never quite see the similarity, – except in this one locality. We could coneivably have been in Devon, in the steep undulations of the Exe Valley. In place of the usual large paddocks were scores of fields. Some were freshly ploughed, lying richly chocolate under the capricious, almost English sky. There were bright green, others golden with ripe barley. In many cases oaten crops had been already stooked.

We came to the top of the hill and there rested and ate chocolate. Behind us Forth was hidden in a vast fold of the hills. Rain appeared to be gaining on us slowly, so we coasted rapidly down from the summit of the Forth Hill, with the picturesque fields on either side. In some were Jersey herds and in others herds of polled Angus bullocks, their black flanks shining.

The steep descent led us into Devonport, lying on the wide estuary of the river Mersey – a mixture of the south of England with the north. An extremely steep descent, – so steep that we decided to go down it on foot, – brought us into a long and busy main street, its neon lights all burning, though it was still daylight.

We had decided that we would go on to Launceston by train the next day, the country ahead appearing to hold less of interest for us than the country east of Launceston. We this end in view we went to the Devonport station and found there that the train left at 8:30 next morning.

…

The journey to Herrick too us five and a half hours, though its distance from Launceston was only about eighty miles by rail and scarcely fifty miles direct.

But we had a compartment to ourselves; the scenery was fine and the weather promising. For the third time, and the last I was conscious of a very distinct resemblance to England. We were in a country of steep, grassy hills through which our train climbed slowly. With thatched cottages the picture would have been complete, – we even had churches with grave yards. This was something we found in most parts of Tasmania. The churches were rarely as picturesque as the old English churches, through there were notable exceptions, but the proximity of grave yards was different from anything I had ever seen elsewhere in Australia.

The guard on the trian took a great interest in us.

“Going to ride from ‘Err’ck” he asked in a breathless sort of way.

“Nice, too; very nice,” he answered himself, “hilly; very hilly. Go by Lotta, of course?”

Where was Lottah?

“Turn off just past Weldborough. Three miles shorter,” he smiled.

At the next station he brought us the Hobart “Mercury”. With him was another man.

“These two are going ‘Err’ck, Bill. Going to ride there to the coast.”

The second man launched into his version of the way to go. On one thing they agreed, – we must go by Lotta.

…

I went into a warped wooden store to ask the way to Pyengana, our goal for the afternoon. Inside rabbit skins hung from the ceiling but no stores of any kind were to be seen.

Pyengana, a shy sort of girl told me, was straight on, – about 17 miles.

She might have told me what else lay ahead.

We dipped immediately into magnificent forest country of tall timber and heavily scented fern gullies. But very soon the way lay up hill. We were forced off our bikes; but the forest was so beautiful, so full of rushing creeks and bird songs that wheeling our bikes was pleasant.

The road continued upward, between its giant trees and dense undergrowth. The fronds of the tree ferns spread above the lesser bushes in a canopy of green. The creek in the valley below us was gowing fainter.

We came at last to a definite crest and immeidately began to coast down. Then strangely, we found ourselves pushing hard, though to all appearances we were going down hill. A man on a bicycle passed us going the other way, coasting freely.

“Are you going downhill, or are we?” I asked bitterly.

“I am,” he laughed, “you’ll have seven more miles of climbing yet!”

When the cyclist was safely beyond hearing I said to Nell, “That’s absurd. I can see by the map that we’re near Weldborough. It will be all down hill after that.”

“Do you think so,” she answered non-committedly.

The cyclist was horribly right. We laboured upwards for a total of three hours. Only then did we coast down into the open country of Weldborough.

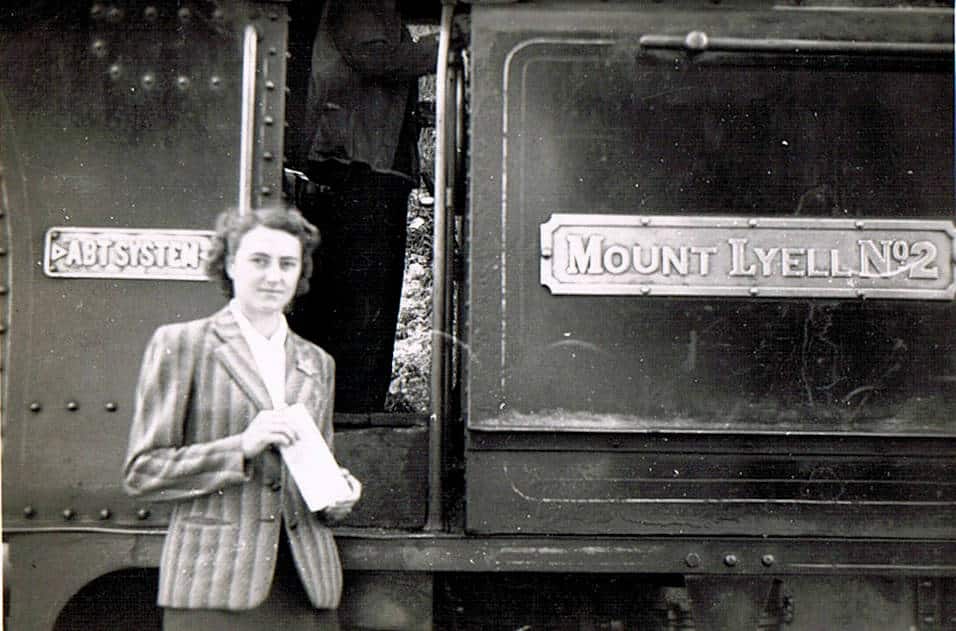

Image: While we don't have the written account, they obviously made it to the West Coast, with Nell pictured next to the ABT train which still operates out of Queenstown today.

...

We only have twenty-seven miles to do,” I said, “even if we laze here till midday we should reach St. Helen’s before nightfall.”

Our climb was really a resumption of the climbing of the day before; but by now we could see the saddle that held promise for us of an end to our troubles.

The day was hot, one of the hottest of our three weeks. The mile posts, it seemed, lay three miles apart. For only about half a mile was it possible to ride. The rest of the journey being solid walking, pushing our loaded bikes.

But the forest was superb. I felt the need of days to wander in its deeps with a camera. Even by the full light of this hot day its ferns and moss and quietly rotting leaves held an atmosphere of overpowering solitude.

Till midday the Weldborough Pass eluded us; but at last we flung down our loaded bikes on the summit. Before us lay a wide panorama of ranges, deep blue beneath a swiftly changing canopy of clouds.

Here, too, was the turn-off to Lotta so loved by the train guard. But our own road descended steeply, whereas the Lottah road promised nothing but jagged stones and level riding. Later we found that for bikes it was almost impassable, though the country it entered was magnificent.

“Do you know what I think of ‘err’ck, the guard?” I said, “I think he talked a Lottah bull.”

Nell made a weak attempt to smile. “Let’s get going. You go ahead, then I can see if there are any bad patches coming up.”

Feeling something of a guinea pig, I began the descent. The bike made alarming attempts to bolt; the gravel spattered against the mudguards; the brake screeched horribly. Once I nearly fell off trying to glance back; but I caught a reassuring glimpse of Nell, braking cautiously, her eyes on the road.

A number of times I pulled up to examine my brake. It was touching the tyre; so I trimmed it a little, then coasted down after Nell.

After coasting for perhaps four miles we met three girls all aged about seventeen. They were riding the opposite way, struggling up through the heat of the day to the Weldborough Pass. They had been almost around Tasmania; this was the last lap.

We noticed they carried practically nothing, except a large fish, apparently for their lunch. It appeared that they sent their packs ahead by bus and picked them up at the end of the day.

When we had coasted further miles and had emerged onto a few level miles, Nell drew up to me.

“That’s a good idea those girls had,” I shouted, “I mean sending their packs on ahead. I think we’ll try it.”